This time, I didn’t pick this pattern from the awful book of Javapocalypse. It’s something I discovered a few years ago when a colleague presented to me RabbitMQ. This technology is a software managing a lot of requests among micro-services by using a message queue. And it’s something very simple but now really important in cloud programming.

In programming, there are many queues: message queue, job queue, task queue, priority queue, command queue, etc. Let’s be simple, and talk about the queue like something calling your functions in the desired order. I’ll present to you the fundamental queue and some of its variations of the base in this article.

The basic version

The queue is a simple structure with two properties: the tasks and a boolean to know if the queue is running. There’s a function to add a new task to the queue and another function to run the queue. So we can easily get this code:

class SimpleQueue {

constructor() {

this.tasks = [];

this.isRunning = false;

}

add(task) {

this.tasks.push(task);

}

run() {

this.isRunning = true;

const currentTask = this.tasks.shift();

// Do something with your task

if (this.tasks.length) {

this.run();

} else {

this.isRunning = false;

}

}

}

export default new SimpleQueue();In theory, it works. In 99% of use cases, it works. But this code has a big problem due to the Javascript call stack. Each time you call a function, you push its information on the call stack. By doing this, your program knows what was and how to return to the previous function. That’s one of the main mechanisms of programming languages.

If we execute our code by adding three tasks and running the queue, we get something like this :

SimpleQueue.add({data: 0});

SimpleQueue.add({data: 1});

SimpleQueue.add({data: 2});

SimpleQueue.run();

// In the queue, a ended run call the next run with the next task

run({data: 0}) {

// Execution of task 1

run({data: 1}) {

// Execution of task 2

run({data: 2}) {

// Execution of task 3

}

}

}The run() function calls itself while there’s a task in the queue. By doing this, we push the information of run function each time on the call stack while there’s a task in the queue. Is the call stack infinite? Of course not. You can execute this code to check the size of the call stack:

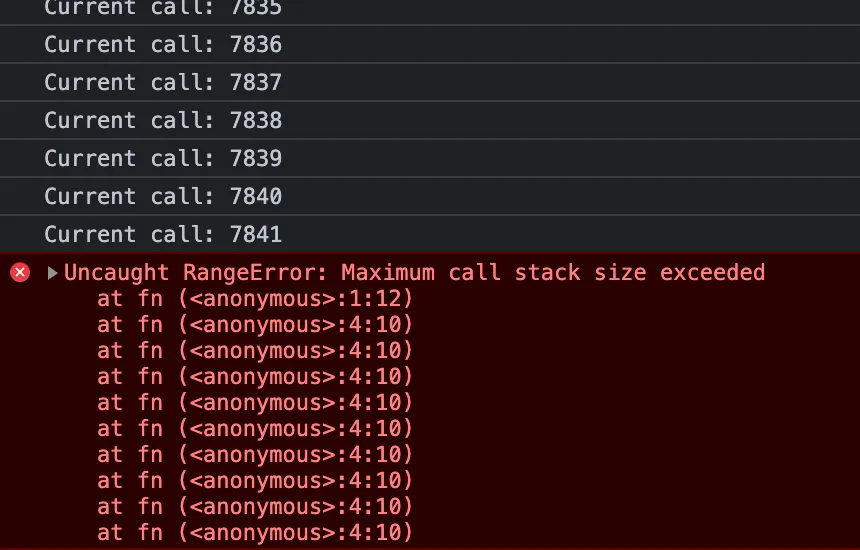

const fn = (i = 0) => {

console.log(`Current call: ${i}`);

return fn(i + 1);

};

fn();

The code execution

In my case, if I run 7842 tasks, I break the program. To fix this, we have two solutions: node.js Events or a good ol’ while loop. We will use the second solution because it works in Vanilla Javascript too.

The code execution

In my case, if I run 7842 tasks, I break the program. To fix this, we have two solutions: node.js Events or a good ol’ while loop. We will use the second solution because it works in Vanilla Javascript too.

run() {

this.isRunning = true;

while (this.tasks.length) {

const currentTask = this.tasks.shift();

// Do something with your task

}

this.isRunning = false;

}So here’s the basic queue which can run for a long time. Maybe you prefer the queue to have an automatic start when a task is added, so let’s move on this code:

class SimpleQueue {

constructor() {

this.tasks = [];

this.isRunning = false;

}

add(task) {

this.tasks.push(task);

// Here's the auto run

if (!this.isRunning) {

this._run();

}

}

// Anything with an underscore is private in my convention

_run() {

this.isRunning = true;

while (this.tasks.length) {

const currentTask = this.tasks.shift();

// Do something with your task

}

this.isRunning = false;

}

}

export default new SimpleQueue();Designing tasks

An essential part of using a queue is to design what is your task. This task is generally a function or an object.

In the case of a function, you have to define:

- the parameters used to call your task.

- the way to wait until the end of a task. If it’s a callback, we have to manage the queue to continue the code when the callback is called. If it’s a Promise, we have to use an

await currentTask()in therun().

class FunctionalQueue {

async _run() {

this.isRunning = true;

while (this.tasks.length) {

const currentTask = this.tasks.shift();

await currentTask();

}

this.isRunning = false;

}

}In the case of an object, you have to define the properties of an object. For example, if I create an HTTPRequestQueue, my object will contain properties like the HTTP method, the URL, the body, the headers, etc.

class HTTPRequestQueue {

async _run() {

this.isRunning = true;

while (this.tasks.length) {

const { url, ...options } = this.tasks.shift();

if (options.withAuthorizationToken) {

if (!options.headers) {

options.headers = new Headers();

}

options.headers.append(

"Authorization",

`Bearer ${ConnectionManager.getAuthorizationToken()}`

);

}

await fetch(url, options);

}

this.isRunning = false;

}

}By using an object, you choose the behavior of your queue due to the impossibility of executing arbitrary code. In other words, using an object is the best way to make a business-specific queue, and using a function is the best way to make a generic queue.

Waiting the end of the queue

The first thing you could need would be to wait until the end of the queue. For example, you want to run a batch of network requests before displaying a success message. In this case, we will use a classic Observer:

class SimpleQueue {

constructor() {

this.endListeners = [];

this.tasks = [];

this.isRunning = false;

}

// To add an observer

onEnd(fn) {

this.endListeners.push(fn);

}

// To remove an observer

removeOnEnd(fn) {

const index = this.endListeners.indexOf(fn);

if (index !== -1) {

this.endListeners.splice(index, 1);

}

}

add(task) {

this.tasks.push(task);

if (!this.isRunning) {

this._run();

}

}

_run() {

this.isRunning = true;

while (this.tasks.length) {

const currentTask = this.tasks.shift();

// Do something with your task

}

this.isRunning = false;

// Call the observers

if (this.endListeners) {

this.endListeners.forEach((observer) => observer());

}

}

}

export default new SimpleQueue();I know callbacks are a bit oldish, so you can extend this code by adding a waitingEnd() function which returns a Promise:

waitingEnd() {

return Promise((resolve) => {

const onEndListener = () => {

this.removeOnEnd(onEndListener);

resolve();

};

this.onEnd(onEndListener);

});

}

// In your code

await SimpleQueue.waitingEnd();Running tasks in parallel

Executing tasks one-by-one can be a bit slow. Maybe you want to run a set of N tasks in parallel. We must reconsider the queue by adding the possibility to run N times the while loop. Javascript is a mono-threaded language, so we don’t have to manage concurrency problems like concurrent modifications of a variable. So here we go:

class ParallelQueue {

constructor() {

this.tasks = [];

// Replace isRunning by runningTasks and maxTasks

this.runningTasks = 0;

this.maxTasks = 3;

}

add(task) {

this.tasks.push(task);

// Start a loop if we're not at the maximum of tasks

if (this.runningTasks < this.maxTasks) {

this._run();

}

}

_run() {

this.runningTasks++;

while (this.tasks.length) {

const currentTask = this.tasks.shift();

// Do something with task

}

this.runningTasks--;

// Call the observers when there's no task

if (!this.runningTasks && this.endListeners) {

this.endListeners.forEach((observer) => observer());

}

}

}Now, you’re the master of the queue. There are many possible extensions to this structure, like adding events at each end of a task, creating rollbacks when a task failed, or anything useful for you.

Thanks for reading! <3

Thanks for reading! <3